| Milking the Jesse Ventura story The Crasher Chronicles |

POSTED OCTOBER 4, 1999--I turn right on to University

Avenue, heading in the direction of Rice street and the State Capitol. It’s 9:15  on

the first Friday evening in October and I’m looking for action. Since I’m

cruising near the Frogtown area of St. Paul, I should say that it’s not the kind of

action that might get my picture on the St. Paul Police department’s notorious Web

site. What I’m looking for is the LIVE action that three-quarter of a million Twin

Cities’ households watch every night at 10 p.m., in the comfort of their own living

rooms. It’s legal, it’s perfectly safe and it’s too silly for words. Which

makes perfect sense, because it’s on the TV news. on

the first Friday evening in October and I’m looking for action. Since I’m

cruising near the Frogtown area of St. Paul, I should say that it’s not the kind of

action that might get my picture on the St. Paul Police department’s notorious Web

site. What I’m looking for is the LIVE action that three-quarter of a million Twin

Cities’ households watch every night at 10 p.m., in the comfort of their own living

rooms. It’s legal, it’s perfectly safe and it’s too silly for words. Which

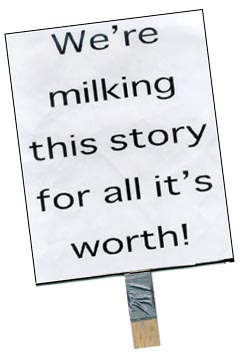

makes perfect sense, because it’s on the TV news.Finding what I’m looking for tonight will depend on one thing: whether or not one of the television stations is craven enough to send a reporter and a crew out on a cold and rainy night to stand in front of the Capitol and introduce video for their lead story about Governor Ventura’s latest flap—his Playboy magazine interview. On a newscast earlier this evening, WCCO reporter Pat Kessler assured viewers that this is a story that is "just going to keep getting bigger and bigger." He neglected to add, "if we have anything to say about it." For that reason, I suspect that one of the stations might lead their 10 p.m. newscast from the Capitol lawn, as WCCO did the previous evening, with the majestic and perfectly lit rotunda serving as the live backdrop. The idea, as with all live reports, is that this will add immediacy and context to a story that for the most part, will be video footage. From the perspective of the local media—all revved-up because they have a national controversy in their own backyard—it’s a story that’s now in a crucial phase; the ‘how big can we make this one?’ phase. The story broke the previous day, with the kind of blockbuster coverage once reserved for either the election of a new governor or the death of a former one. But those arcane rules no longer apply. Like Hollywood, the plan is to have one very big story playing on as many screens as possible, and by all means, make sure you have a good opening weekend. On day two of this story’s opening weekend, things are looking pretty desolate as I circle the Capitol and turn on to the street that runs parallel to and directly in front of it. There are just a few cars parked at the long row of meters on the left side of the street and I decide to diagonal into one of the parking spots. This places me facing away from the Capitol, looking across a huge expanse of lawn. Across that lawn, I notice a couple of people milling around a van with its side doors open. I get out of the car for a closer look, and although there appears to be a bank of televisions in the van, I can’t quite make out the lettering on the side of it. I decide to do yet another circle by car to find out if it’s what I’m looking for. Sure enough, "The Hometown Team" is emblazoned on the side of the van and WCCO is getting ready to use the same live shot that opened their newscast the previous evening. Once again, they will remind viewers that the office is bigger than the man. What I’m reminded of, is that the Capitol dome bears a striking resemblance to the head of our governor. Now that I’ve found the live action I’ve come here looking for, this is what I plan to do: When the camera starts rolling, I’ll run across the lawn, stop a few feet behind the reporter and hold up a sign. The words on the sign were typed earlier this evening, blown-up at Kinko’s, and then spray-mounted onto a piece of cardboard. The sign is about two-feet wide and three-feet high and it says, "We’re milking this story for all it’s worth!" If my timing is perfect, a few-hundred-thousand people watching at home will get to see what I think about media coverage of the latest Jesse Ventura brouhaha. In addition, a few people here, along with many more at WCCO’s studios in downtown Minneapolis will get very pissed. Hopefully, many viewers will be thinking the same thing I am, and for a glorious few seconds, it will feel like pay-back time for all of the overblown and sensationalized reports that consumers of television news regularly endure.

At five minutes before 10 it’s time to move. Since I’m too far away to make a run for it once they go live, I need to get closer to the action. Besides, there is not another soul in sight, and if they see someone with a big-ass sign walking toward them across a deserted lawn, they might suspect that it’s me. The last time I walked on to a WCCO newscast, also on a Friday night, the shooter came out from behind his camera and tried to tackle me. If it’s the same guy, he might spot me charging across the lawn and intercept me before I can get anywhere near the reporter. Off to my right there’s a street that borders

the lawn, curling in a downward slope towards the van, where the lights illuminating the

reporter have now been turned on. Half-way down that street is a bus-stop, which will get

me to within about thirty yards of my goal. I grab the sign, along with the pocket

television and I’m on my way. When I get there I notice a tree about ten yards away,

in the direction of the reporter. Scrambling toward the tree, but careful to remain hidden

behind it, I am now within striking distance. As I lean my sign against the back of the

tree, I glance at the television, just in time to hear n There are two schools of thought about when to walk on to a live broadcast. When they initially "go live," the reporter will usually be on-screen for 10 to 15 seconds, introducing the video footage. That footage might run for anywhere from 30 seconds to a couple of minutes, and then they will cut back to the reporter, who will wrap up the story, usually talking for about twice as long as the first time. The obvious advantage of walking on to the second segment is that you have more potential air time and more time to maneuver. The disadvantage is that when the report ends, you are standing there with three or four extremely angry people, determined to make you pay for your 15 seconds of fame. After showing video clips of numerous people calling for the head of the governor, they cut back to the reporter. At this point, I make a mistake that will come back to haunt me: I hesitate, for just a couple of seconds, asking myself, "Is it possible to cover that much distance before the report ends?" Then I begin my mad dash toward your living room. I get right behind the reporter, as planned, but there are problems from the beginning. The shot seems very tight, as if the reporter is superimposed on the Capitol. As soon as I pull-back a bit to try and capture some more screen, the cameraman leaves his position and comes after me, just like the last time, crab-walking and pushing me out of the way from underneath, so as to keep himself out of the picture. It appears to be a different cameraman than the one who charged me before, but it’s the exact same move, and I have to wonder if they’ve all spent an afternoon somewhere practicing this technique. As suddenly as I entered it, I’m sent spinning out of the picture. But like the cameraman, I’ve also learned from my experience and manage to spin away from him. Once again, I’m back in the picture lunging towards the reporter, and this time there’s no one behind the camera to zoom me out. It’s just me and John Reger! But I’m rattled, and I have a difficult time figuring out where to hold the sign. As I pull back the sign, which I should have done sooner, the lights suddenly go off and the report is over. Now it’s just them and me, with no chance for a clean get-away. First the cameraman comes at me and starts shoving. He’s fairly gentle though, just pushing me away, apparently unable to shake his well-practiced on-air technique. As I’m retreating, a huge man comes charging at me from near the van. He’s not at all gentle as he grabs me hard by the shoulders and the back of the neck and starts shaking me, screaming, "Get the fuck out of here. Get the fuck out of here." I shake him loose and stumble away, yelling at everyone that this is public property and I have as much right to be here as they do. "You’re out here every week," he says. "What the fuck’s wrong with you?" I want to tell him that I haven’t been "out here" in more than a month, and to ask what the fuck’s wrong with him, since he’s out here every night. But I just blurt out: "I’ve got a message and I’ve got a right to deliver it, just like you." Of course the only message he’s interested in delivering is to get the fuck out of here, and quit making his job a pain in the ass. And for now, that’s what I do. If there is a weak link in my resolve, it involves disrupting the work of the people shooting and reporting the live remotes. Other than guilt by association, I have nothing against any of them personally. It’s not primarily their fault that television news is so awful—they’re just doing a job. But my resolve in that area is strengthening as I continue to be assaulted by the camera and technical people, who I am now coming to think of as goons. When I arrive home, my television is still turned

on and David Letterman is delivering his monologue. I am too anxious to watch for any 38DD

bra jokes, and immediately rewind the tape in the VCR, prepared for the worst. I’m

not very hopeful about my chances for success this evening and the tape proves me right.

Everything happened exactly as I had imagined, only worse. The sign was too close to the

reporter the first time around, and then I was pushed off-screen before having time to

adjust. And when I returned, more signage problems. It’s an embarrassing performance

and a missed-opportunity to deliver a message—my message— to hundreds-

of-thousands of unsuspecting viewers. Surprising and hopefully amusing the audience at

home is the most exhilirating part of all, since they have come to expect newscasts that

are machine-like in their efficien Of course there will be plenty of other opportunities to walk on to live remotes and exercise my freedom of speech. They’re obviously not going away and neither am I. But colder weather is coming—another test of my resolve—and the live reports will be fewer and farther between. Or will they? As I watch the tape over and over, looking for any possibility that an eagle-eyed viewer might have been able to decipher a message out of the blur, I notice that John Reger is wearing a very heavy coat. And I realize that in rain, or sleet or snow, especially snow, the live reports must go on. |

I’m

now back where I started: sitting in my car across the street from the front of

the Capitol, staring across that huge lawn and trying to figure out how to "sneak-up"

on someone standing at least 50 yards away. There’s nothing between us but

the massive spotlights illuminating the Capitol building and a whole lot of grass.

Since I last circled the block to inspect the van, a sport-utility vehicle has

pulled in behind it. This is a sure sign that "the talent" has arrived.

I turn on my portable TV with its 2" square screen and check-out the reception.

Usually when I’m getting ready to walk onto a live broadcast—see

I’m

now back where I started: sitting in my car across the street from the front of

the Capitol, staring across that huge lawn and trying to figure out how to "sneak-up"

on someone standing at least 50 yards away. There’s nothing between us but

the massive spotlights illuminating the Capitol building and a whole lot of grass.

Since I last circled the block to inspect the van, a sport-utility vehicle has

pulled in behind it. This is a sure sign that "the talent" has arrived.

I turn on my portable TV with its 2" square screen and check-out the reception.

Usually when I’m getting ready to walk onto a live broadcast—see  ewsreader Don Shelby say, "WCCO’s John Reger

is live from the Capitol with more tonight...John."

ewsreader Don Shelby say, "WCCO’s John Reger

is live from the Capitol with more tonight...John." cy,

and absolute in their control of the reporting environment.

cy,

and absolute in their control of the reporting environment.